In the summer of 1986, I house-sat for my girlfriend Laurie as her family traveled to Kenya and Tanzania to go on safari. As a zoology major of course I was jealous, but I was also worried; I am neither superstitious nor prone to premonitions, but I envisioned Laurie’s always well-intentioned but often overzealous father somehow suffering an injury during a scheduled hot-air-balloon ride over the Serengeti.

Unfortunately my hunch was accurate; the balloon crash-landed, and my now father-in-law managed to fall out of, and under, said balloon before being crushed by its basket, breaking a clavicle, and leaving an earlobe on the plains of Africa. He was subsequently airlifted so that he could receive proper medical attention, and eventually recovered nicely (we now fondly refer to his lobe-less ear as his “earlet”). The remainder of their trip transpired in a remarkably peaceful fashion, and, despite The Misstep on the Masai, I remained thoroughly envious of their experience.

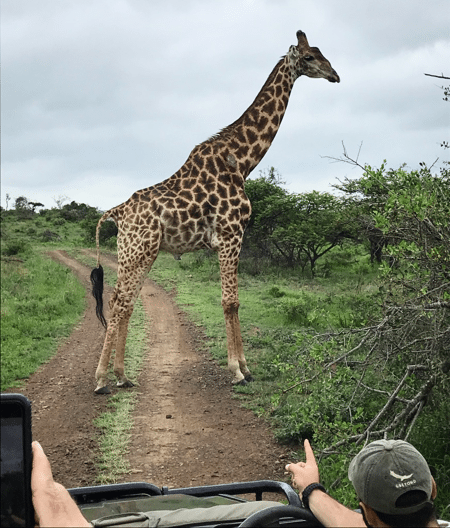

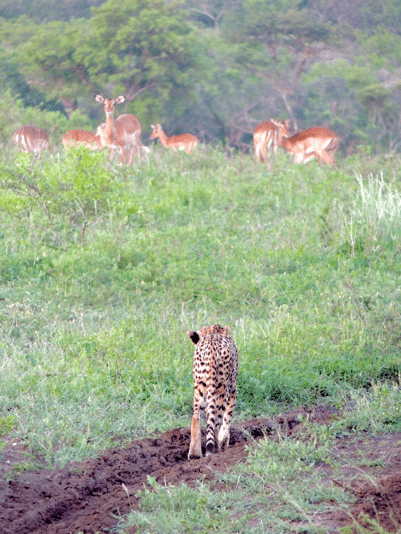

Fast-forward thirty-one years, and I also became lucky enough to participate in a safari, this time in South Africa and this time without an unplanned visit to the hospital. Though I was able to mark this once-in-a-lifetime trip off my own bucket list, perhaps its most resonating takeaway was not the breathtaking scenery, or even breathlessly (through excitement, not on foot) chasing a cheetah on an impala hunt.

Instead, I was most struck by the passion and devotion of the rangers and trackers of the private game reserves of Phinda and Ngala. As part of their induction to the bush, rangers-in-training take a nine-day hike alone through a reserve with only a rifle, a little food and water, and a helluva lot of bravery. To this chickenshit, who, in his own small way, conquered the reserve by having a lion saunter only a few feet from his vehicle without peeing his pants, the thought of completing such a mission is beyond comprehension.

One particular ranger, Lee-Anne Davis of the Ngala reserve, tirelessly embodies the collective spirit of the rangers and trackers, not just through her willingness to off-road a Landrover through thicket for two hours to catch that unforgettable glimpse of an elusive leopard. She also smartly and rationally seeks to affect systemic change through her organization, Our Horn is Not Medicine, a nonprofit devoted to the preservation of rhinos through education, protection and relocation.

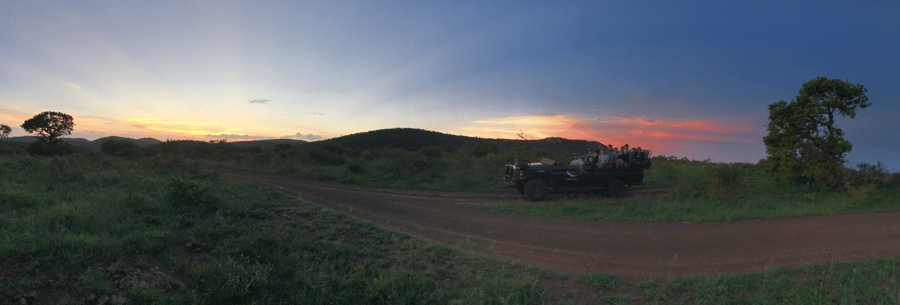

The end result of this bucket list item was an unforgettable trip, a bunch of great photo ops (admittedly once while listening to Toto’s “Africa”), and an enhanced appreciation for South Africa and for those who seek to preserve its natural beauty. To learn more about Our Horn Is Not Medicine, and how to donate to the organization, click here.

Leave A Comment